From commercial design to independent artistic practice, from memories of the four seasons to the Spirit of the Horse collection Mã Niên, Phan Linh’s creative world is where tradition, personal sensibility, and a sense of freedom converge.

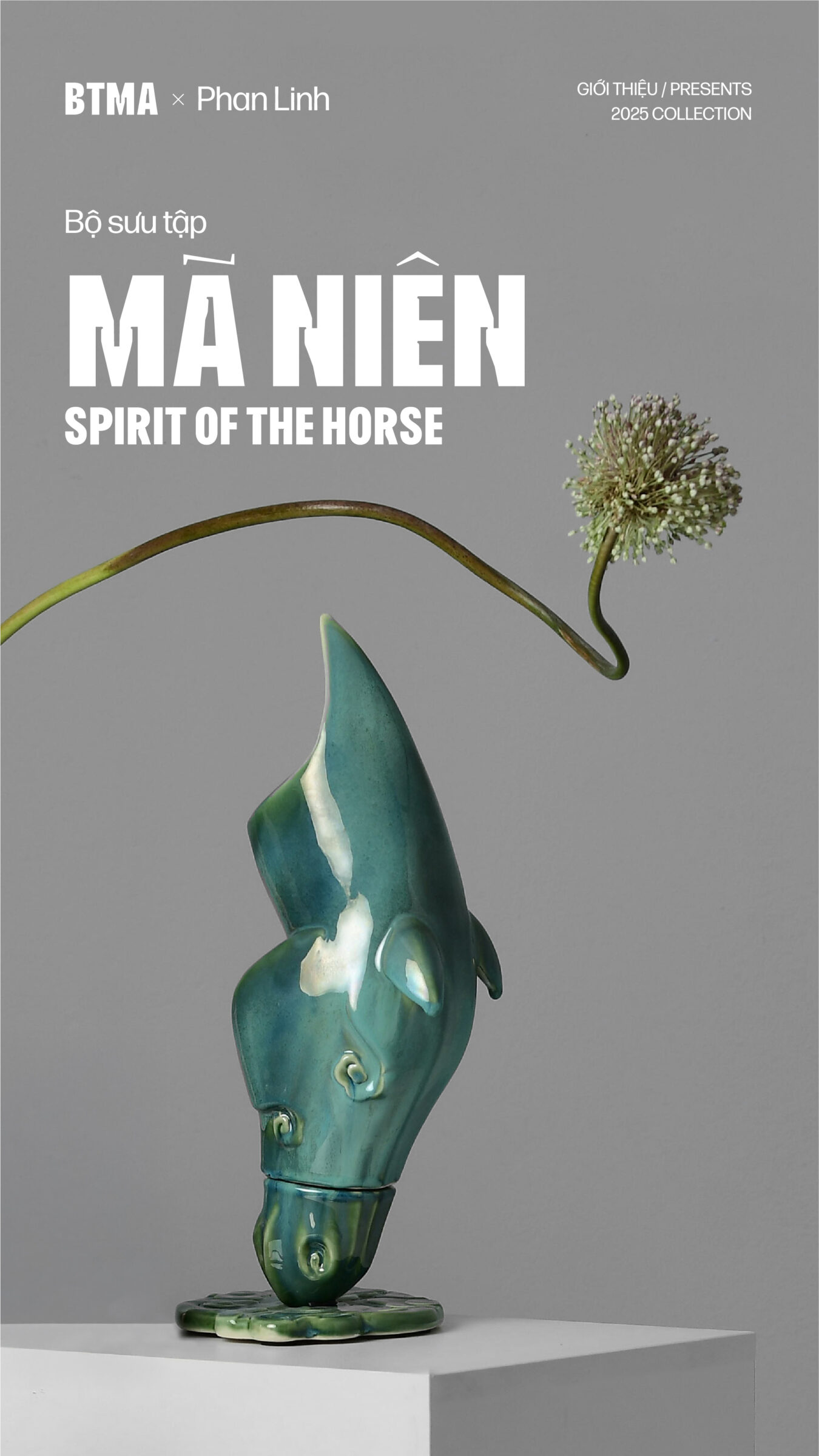

A contemporary artist with more than two decades of experience in visual arts and creative design, Phan Linh has recently unveiled Mã Niên, a collaborative collection with Bát Tràng Museum Atelier, shortly after the closing of her solo exhibition Perpetual Flows. Together, these projects mark a series of significant milestones in her artistic journey.

A CREATIVE CONNECTION WITH BÁT TRÀNG MUSEUM ATELIER

Could you share how your collaboration with Bát Tràng Museum Atelier (BTMA) began?

I have worked with Vũ Khánh Tùng, Creative Director of Bát Tràng Museum Atelier, since 2008. At the time, I was serving as Art Director for Sành Điệu magazine, while Tùng worked as a producer, overseeing fashion photo shoots for various publications. Over the years, our long-standing friendship has fostered a deep mutual understanding in how we work.

Around 2014, I gradually began experimenting with product design, working across materials such as lacquer, ceramics, paper, and bamboo. After closely observing Tùng’s journey in carrying forward Bát Tràng Museum and developing BTMA, we decided to collaborate on Mã Niên—a symbolic design for 2026 that marks the transition between the old year and the new.

What role does ceramics play in your creative practice?

Ceramics are a sustainable material, rich in memory and deeply embedded in Vietnamese daily life. Each craft village has its own distinctive clay and glaze, shaping a strong regional identity. Through my experiments with lacquer on ceramics, I came to appreciate the material’s durability and longevity. I am drawn to materials that carry such depth.

THE MÃ NIÊN COLLECTION

How did the concept and form of the Mã Niên collection take shape?

The inspiration came from Kim Ki-duk’s film Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring, which reflects the natural cycle of time. Living in Northern Europe—where winter lasts seven to eight months—made me deeply miss the seasonal transitions of Hanoi. I wanted to translate that feeling into the design of the Mã Niên horse sculpture.

The horse’s form draws from traditional architectural motifs. I envisioned a horse pausing to drink water in an open field. The water surface is interpreted through the lines of a saddle found in stone sculptures at the Minh Mạng Tomb (19th century), combined with cloud patterns familiar in Vietnamese art. As the horse gazes into the water, I imagine it drinking in the sky itself—absorbing nature across spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The Mã Niên sculpture is composed of three detachable sections, allowing the glaze tones to shift according to space.

The collection was developed with a strong focus on everyday functionality, with the horse sculpture as its centerpiece. From there, it expands into practical objects such as coffee cups, noodle bowls, vases, and coasters. In the next phase, the project continues with the development of a table lamp. All designs are derived from details of the horse’s form, reinterpreted through a contemporary lens.

The horse appears frequently in global art history, in many different forms. What draws you to this image in your work?

The horse has been intertwined with human life since ancient times, appearing throughout history. From the horse heads of the Parthenon in Greece to contemporary interpretations such as The Kelpies by Andy Scott, or the contemplative equine works of Nic Fiddian-Green (Still Water), Tom Hiscocks (Drinking Horse), and Antonio Signorini (Oiram), the image carries many layers of meaning. Yet when returning to Mã Niên, crafted in Bát Tràng ceramics, the narrative shifts. It becomes more intimate, familiar, and distinctly Vietnamese.

ENERGY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Has your workload in Norway changed compared to before?

Previously—especially toward the end of the year—the workload was intense and often left me feeling exhausted. At one point, I realized I needed to slow down. After stepping away from my work in window display, I spent months walking in forests, foraging, and simply being in nature. Nearly an entire year was devoted to rest and renewal.

How do you maintain creative energy today?

Norway’s climate makes gardening challenging, but I still tend a small garden each summer. Otherwise, I devote most of my time to art—that is how I best recharge.

After more than 20 years in the creative field, what led you to move from commercial design to independent artistic practice?

Design and artistic creation are fundamentally different. Design responds to external needs, while artistic practice is a process of turning inward, expressing personal emotion and experience. That said, the two complement each other. Years of design work gave me a strong technical foundation. When I moved into independent practice, I realized that anchoring my work in traditional values was the most natural path forward.

Traditional craftsmanship and the preservation of craft villages over time are central to my practice. For me, sustainability is not only about reusing materials, but about safeguarding and carrying forward cultural values so they can continue to exist in contemporary life. Craftspeople and farmers working in endangered traditions—such as Lãnh Mỹ A silk or dó paper from Yên Thái—constantly remind me of the urgency to protect this heritage. Observing similar concerns in countries like Norway and France, I see that this is not a personal interest, but a shared global movement.

What did your recent solo exhibition Perpetual Flows represent for you?

Perpetual Flows marked the beginning of a new chapter. The works interweave graphic design and classical photography. I am drawn to the way tradition and modernity can merge to form a new visual language. The exhibition opened doors to future projects.

What do you hope to pursue next?

I am continuing to explore painting and materials within product design. I am also developing an idea for a large-scale installation using discarded materials, in collaboration with craft villages such as Bát Tràng (ceramics), Ngũ Xã (bronze), and Hạ Thái (lacquer).

Ultimately, I seek freedom—the freedom to work openly and honestly, and to do what I truly want in art.

Thank you for sharing!

Hanoi, December 2025

An exclusive interview for Bát Tràng Museum Journal