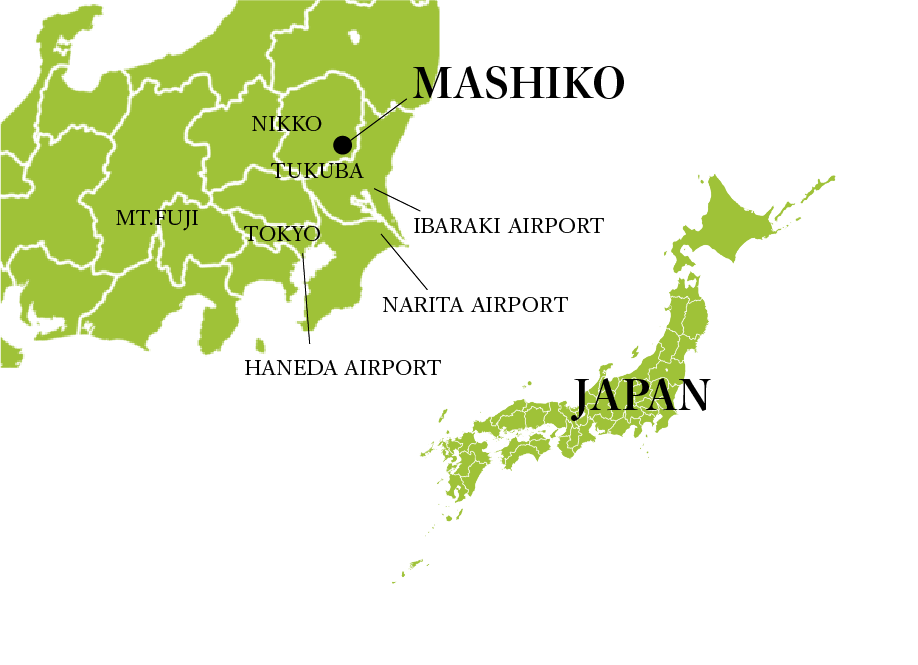

Late autumn brought me on a journey to Japan with Bát Tràng Museum Atelier. Over the course of two weeks exploring the country, we had the privilege of visiting the renowned pottery town of Mashiko.

Before arriving, I held a common but misguided assumption: that the Japanese were often reserved and hesitant around strangers. My past encounters felt like cordial exchanges—polite but never quite reaching true connection.

Mashiko, however, shattered that perception.

From our first encounter with Mr. Nobuya Aigun—advisor to the historic Tsukamoto Kiln—we felt sincerely welcomed. His warmth quickly dispelled the frustration caused earlier by our interpreter who had led us in circles around the town trying to locate him. It turned out Mr. Aigun had graciously agreed, through a brief message from a mutual friend in Tokyo, to give us a private tour.

Rewinding Time and Memory

Our walk through Mashiko began with Mr. Aigun recounting the town’s history. Pottery production in Mashiko began in 1853, during the final years of the Edo period. Thanks to its proximity to Tokyo, the area quickly evolved into a center for functional ceramics. At the time, Mashiko ware lacked a defining style—it was primarily utilitarian. The local fine clay made it ideal for creating lightweight wares for daily use. It was even said that thousands of Dobin teapots¹ were decorated every day.

But what transformed this humble pottery town into a hub of ceramic art?

“Art Begins in the Everyday”

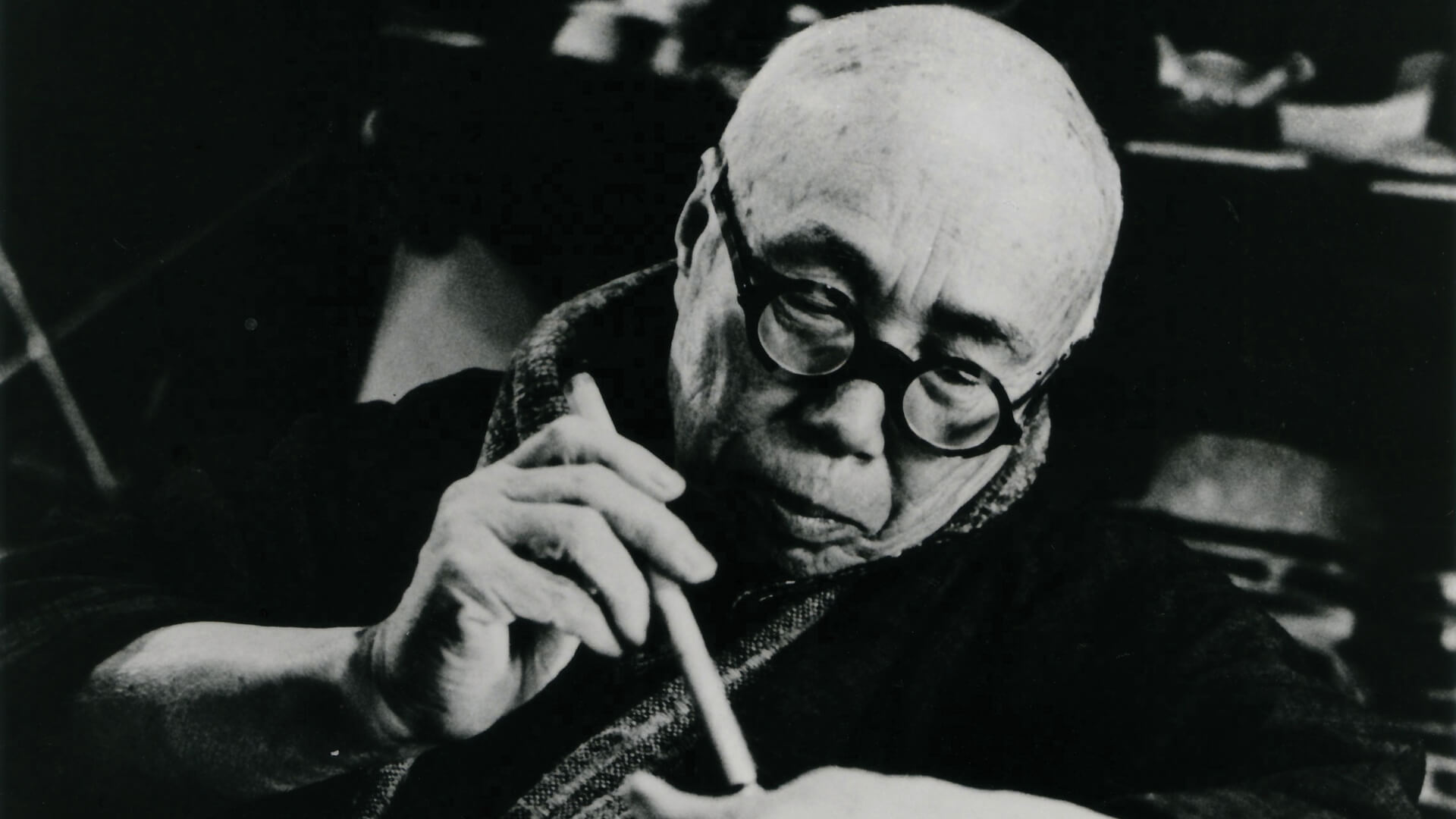

That transformation came in 1930, with the arrival of Shōji Hamada—later declared a Living National Treasure (Ningen Kokuhō)² of Japan. Hamada had just returned from England, where he had collaborated with Bernard Leach at the Leach Pottery in St. Ives, Cornwall, and held his first solo exhibition at the Paterson Gallery in London in 1923.

Following a devastating earthquake in Kantō that same year, Hamada decided to return to Japan, first visiting Mashiko in 1924, and settling there permanently in 1930.

Hamada brought with him not only technical knowledge but also a philosophy deeply rooted in East-West aesthetics, folk art values, and personal expression. Through his practice, he elevated ordinary wares into art, blending function with beauty, tradition with innovation.

His legacy inspired waves of artists to move to Mashiko—especially in the 1970s—turning it into a creative haven for ceramicists from across Japan and beyond.

“Inheritance and Growth” at Tsukamoto Kiln

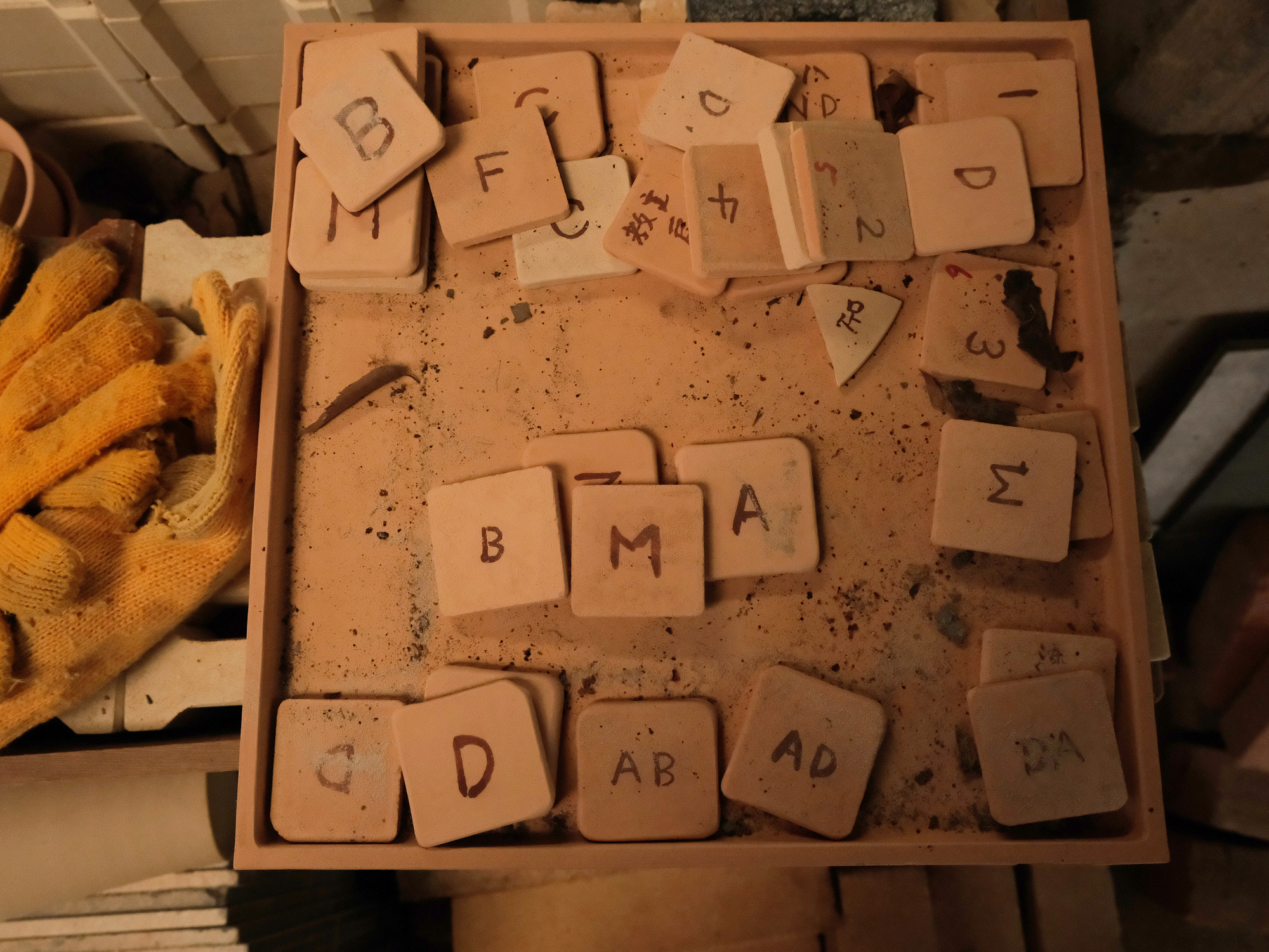

Back at the Tsukamoto workshop, Mr. Aigun—steeped in the spirit of Rihei Tsukamoto³—shared every detail of the production process for the traditional Kamakko⁴ rice bowl. From machine-made stages to hand-finishing and kiln temperatures, nothing was held back.

We were astonished to learn that 8,000 Kamakko bowls are produced here daily. But beyond numbers, the workshop’s aesthetic—the harmony of tools, clay, and light—was captivating. Every corner looked like it belonged in a frame.

In Mashiko, pottery classes led by master artisans are held regularly. We ended our workshop visit at the Tsukamoto showroom, which also functions as a retail space, featuring works by Mashiko potters—including masterpieces by Shōji Hamada and his disciple Tatsuzō Shimaoka⁵.

Shoji Hamada Memorial & Sankokan Museum

Our final destination was Hamada’s former residence, now the Mashiko Sankokan Museum. Here, we learned that Hamada was not only a potter but also a thoughtful designer. In 1930, he restored a traditional compound—relocating old Edo-era houses to Mashiko—and curated an environment that now serves as both a living museum and a reference library of his life’s journey.

Each room displays his personal collection of furniture, tools, ceramics, and folk objects from his travels. The name “Sankokan” (meaning “reference hall” in Japanese)⁶ encapsulates his wish for future generations to draw inspiration, yet forge their own paths—just as he did.

Visitors can now walk through his thatched-roof house, officially opened to the public as a cultural site in 1989.

As we walked back to the parking lot en route to the train station, I spotted a sign reading: “St. Ives 9,803 km.”

“That’s the distance to his first kiln in England, shared with Bernard Leach,” Mr. Aigun said, marking a poetic end to our journey.